How To Talk With Family And Friends About Politics

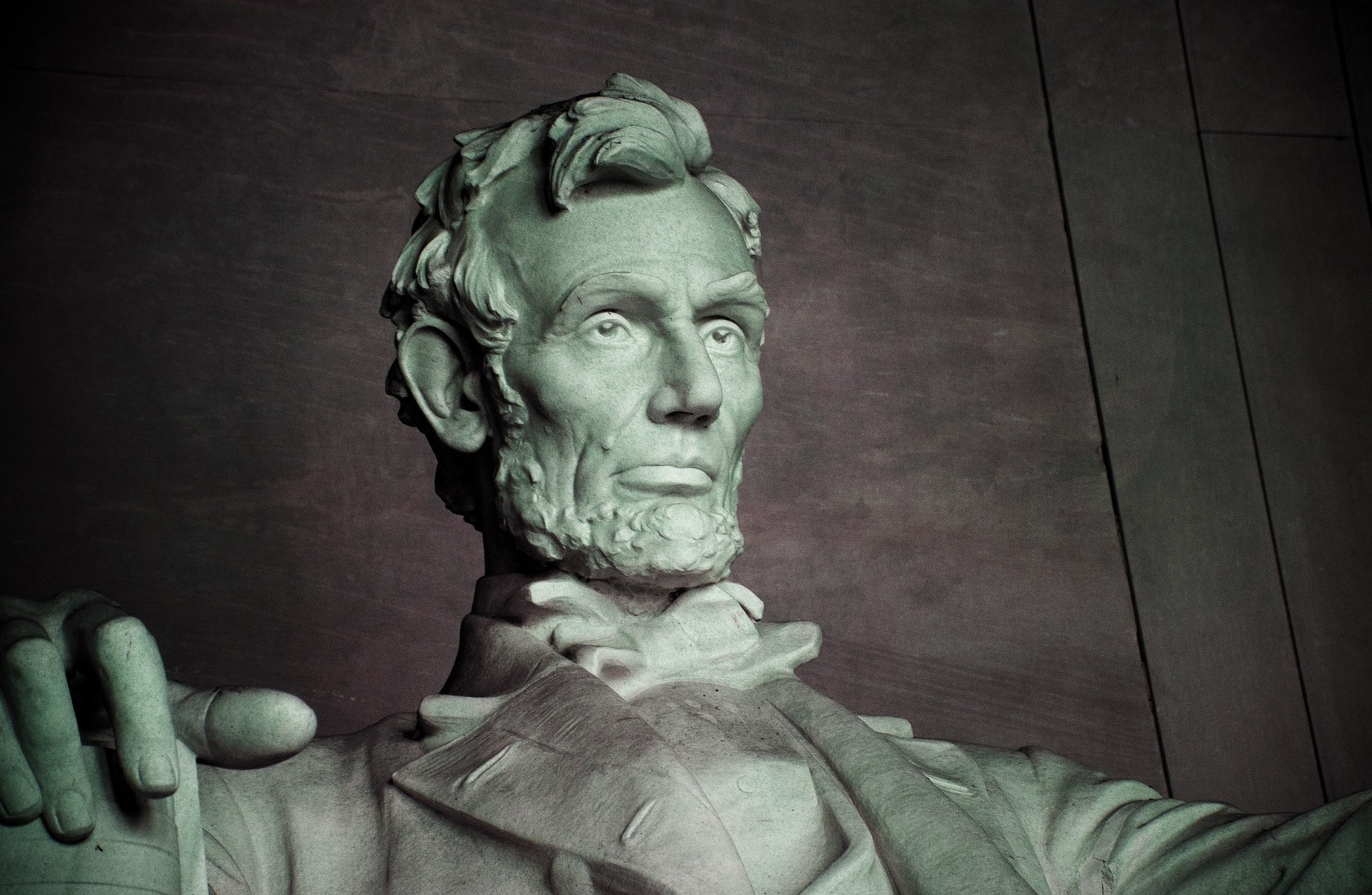

While it may seem like politics has gotten more fractured in recent years, the truth is that politics has always been a divisive topic among families. Benjamin Franklin, one of the fathers of the American Revolution, famously had a falling out with his son William, a British Loyalist, and the two never really reconciled. Families during the Civil War were likewise split over the election of Abraham Lincoln and the secession of the South.

For many people, the solution is to not talk about politics with family or even friends. And in many cases that might be a wise idea, especially if it could lead to a real divide in the household. Letting your aunt or uncle rage against the candidate you voted for isn’t always fun, but it is sometimes the best course when it comes to keeping the family peace. Same for that friend who was really cool in college but has since developed a partisan streak you didn’t expect. (In my view, always stay away from political debates online, as they almost never accomplish anything.)

Sometimes, though, it might not be desirable or possible to stay silent, and for any number of reasons. If you do decide to dive into politics, here are a few things to keep in mind.

Seek to understand.

If you’re going to forage into a discussion on politics, you need to know what the other person believes and why … and the why is important. It’s very easy to dismiss people as being narrow-minded or bigoted, but the truth is that many people have deeper reasons for believing what they do, even if it’s not clear why.

Let me give you two examples from my own family to illustrate: my two grandmothers. Both were part of the “Greatest Generation” who grew up during the Great Depression, married World War II veterans, and raised four Baby Boomer children. The two women died in the early 2000s, within two years of one another.

One was a lifelong Democrat. I asked her once who she would vote for if Adolf Hitler was running as a Democrat. She told me she wouldn’t vote.

The other was an avowed Republican. She listened to conservative radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh religiously and proudly proclaimed to me that “Rush is right!”

It would have been easy to dismiss them as older ladies who were set in their ways. But as I grew older I started to better understand why they believed as they did. My Democratic grandmother, who was born in 1918, came of age in the era of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt and admired his New Deal programs; that loyalty continued for the rest of her life. My Republican grandmother was raised as a nominal Presbyterian but became, along with my grandfather, a devoted evangelical who thought highly of Ronald Reagan and worried about what she saw as moral decline in America.

Those “whys” were important for me, as they helped me understand them when I talked with them … and knowing the background of your own friends and family can help you, too. It can help you choose your words more carefully, and even give you opportunities to ask questions that deepen your understanding of your family and what shapes them.

A useful tool to put this to use: when the person explains themselves, be willing to restate their own opinion back to them. “As I understand it, you believe that …” Now, be careful here — you don’t want to build what’s called a straw man, or a position that isn’t what the person actually thinks. Instead, you want to be able to clearly articulate what they think as well as they could articulate it. This shows that you heard what they said, understand it, and value their opinion enough to make sure you understood it correctly.

Draw from personal experience.

Most people will tell you that political debates never convince anyone. And they’re largely right. Research shows that presenting other people with facts — even compelling facts — often does almost nothing to change anyone’s mind. All those social media debates have basically accomplished … well, nothing. There are a whole lot of reasons this happens, but one reason is rooted in how our beliefs are a way we see ourselves as members of certain groups. In other words, for us to admit we’re wrong about a subject is like stripping away, psychologically speaking, part of our identity. It threatens our very membership in a group we see ourselves as a part of. While it’s possible for people to change their minds on their own terms, people don’t take well to having others try to force them from their positions, no matter how many facts the other side has.

What *can* be more effective, though, is drawing from personal experience. Just as it’s important to know the background of your family and friends when you seek to understand them, it’s also useful for them to see what drives you. Rather than bombard them with facts or statistics or rational arguments, explain why the stakes are important to you.

Share a story about someone you care about who was affected, positively or negatively. Talk about how a specific policy has changed your life. Talk about what a specific issue means to you. Let them see that this isn’t just about facts, but that this is about you as a person.

Look for common ground.

Years ago I remember sitting around with a group of 50- and early 60-somethings talking about health care. This wasn’t just some abstract conversation about whether X was right or Y was wrong — it was a poignant conversation with people who were grappling with the difficulties of the American health care system. What was interesting is that everyone, regardless of their political stripe, knew that something was wrong with the system … even if they may have disagreed about how to fix it.

There are certain things you can do in a political conversation that can make a difference, and one of them is looking for common ground.

That starts with a few magic words: I don’t have all the answers. That means you’re acknowledging that you don’t know everything and you could be wrong. This is a good way to build some common ground because you’re telling them you’re willing to be flexible … which may help them also be a little more flexible.

Beyond that, talking about areas of agreement is also worth considering. Do you both agree on the problem? Talk about that. Do you both agree on some parts of the solution? Talk about that. Do you both agree on what isn’t the solution? Talk about that.

What about you? What’s worked, or not worked, in your conversations with friends and family?